Your Read is on the Way

Every Story Matters

Every Story Matters

The Hydropower Boom in Africa: A Green Energy Revolution Africa is tapping into its immense hydropower potential, ushering in an era of renewable energy. With monumental projects like Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and the Inga Dams in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the continent is gearing up to address its energy demands sustainably while driving economic growth.

Northern Kenya is a region rich in resources, cultural diversity, and strategic trade potential, yet it remains underutilized in the national development agenda.

Can AI Help cure HIV AIDS in 2025

Why Ruiru is Almost Dominating Thika in 2025

Mathare Exposed! Discover Mathare-Nairobi through an immersive ground and aerial Tour- HD

Bullet Bras Evolution || Where did Bullet Bras go to?

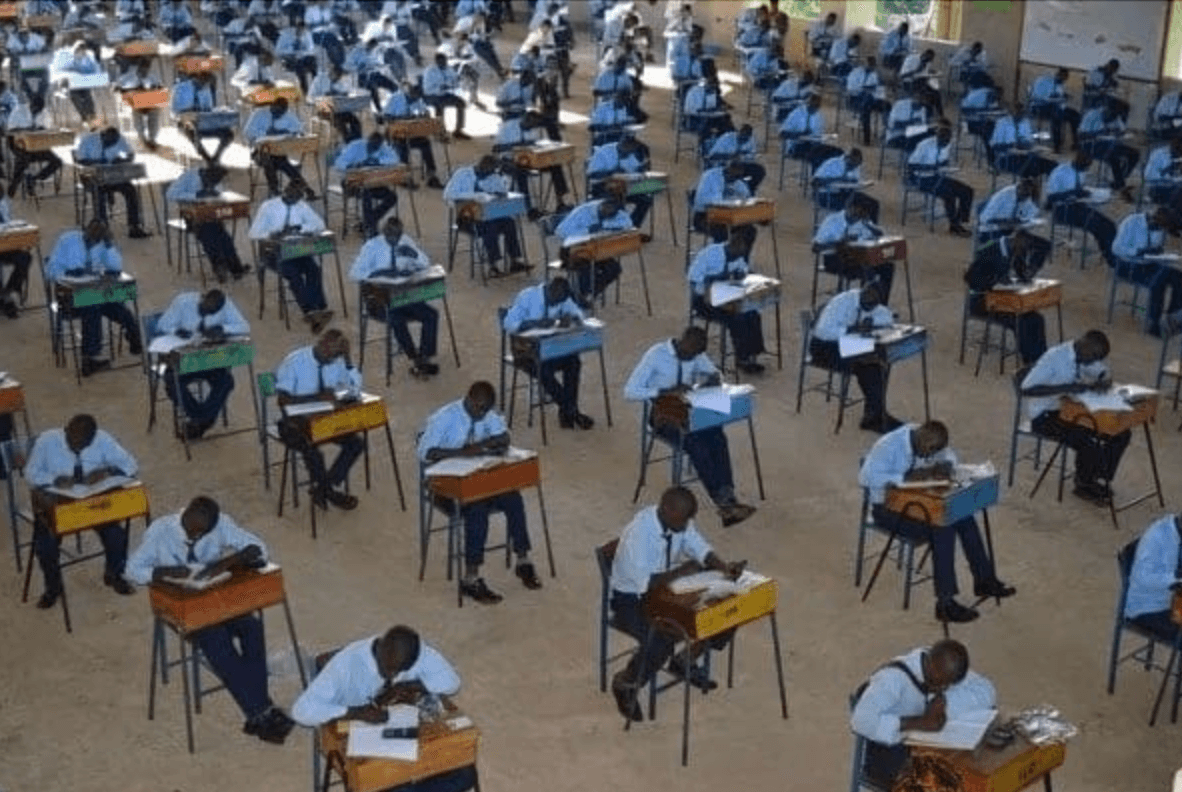

Kenya is embarking on what may become one of the most audacious educational reforms in its post-independence history. In a climate thick with political disillusionment and national fatigue, Suba South MP Caroli Omondi has proposed embedding Nationhood Science into the national curriculum. His vision is clear: educate young Kenyans in the fundamentals of patriotism, citizenship, and governance, not as a one-off lecture or elective topic, but as a core subject that follows them throughout their academic journey.

For Omondi, this is not about adding another subject for examination—it’s about rewriting the contract between the state and its citizens. And that contract, he argues, must start in the classroom.

Kenya’s political system, Omondi believes, is deeply flawed—not because the Constitution is broken, but because the values enshrined within it have never truly been internalized. Decades of tribal politics, institutional distrust, and self-serving leadership have corroded public confidence in governance. The result is a disjointed populace, quick to vote but slow to engage meaningfully in nation-building.

Nationhood Science is conceived as a response to this civic disconnect. The subject would teach national history, constitutional principles, citizen rights and responsibilities, and governance processes. It would also focus on real-world applications: student parliaments, debates, service learning, and policy simulations. The goal is to go beyond theory—students should live their lessons.

Omondi’s idea is not without precedent. Singapore’s Social Studies curriculum, mandatory in secondary schools, is meticulously designed to cultivate social cohesion, a sense of national belonging, and political literacy. Sweden's Samhällskunskap ensures students understand democracy not as a concept, but as a lived, practiced reality.

Both nations, in their own contexts, have successfully used education to reinforce collective identity and civic consciousness. Kenya, facing the twin crises of institutional decay and political apathy, appears ready to test a similar model.

While the proposal is framed in the language of education, its subtext is a damning critique of Kenya’s leadership class. Omondi lays much of the blame at the feet of political parties, which he accuses of prioritizing loyalty over merit. Rather than nurturing statesmen, these parties elevate individuals driven by ambition, not vision. This culture, he contends, breeds leaders unfit for diplomacy, economic strategy, or ethical governance.

Nationhood Science, then, is as much about counterbalancing a failed elite as it is about empowering future generations. It is a strategic bet: that by educating the young differently, Kenya can ultimately govern itself differently.

But ideas, no matter how noble, face the rigors of real-world implementation. The proposal will need to clear several hurdles:

Curriculum Design: Crafting content that reflects national values without veering into ideology.

Teacher Capacity: Training educators who can teach governance and ethics with both authority and neutrality.

Resource Allocation: Securing the financial and institutional support to introduce a subject across all educational levels.

Ideological Safeguards: Preventing political misuse of the subject to favor ruling narratives or suppress dissent.

These challenges are non-trivial. But they also present an opportunity—to rebuild public trust in education and governance simultaneously.

If successful, Nationhood Science could serve as the glue for Kenya’s fragmented national identity. Students would not just pass through schools—they would emerge as critical thinkers, engaged citizens, and informed participants in democracy.

This transformation is not merely academic. A more civic-conscious population could translate into better voter turnout, more issue-driven elections, and broader civic participation. It might even slow the brain drain by convincing young Kenyans that their country is worth staying for—and fighting for.

There is still skepticism. Can a curriculum truly instill values? Or is this simply an overreach—a bureaucratic attempt to fix a moral and political crisis with textbooks? Omondi insists it’s neither idealism nor indoctrination—it’s necessity. But for the proposal to succeed, it must be shaped not just by politicians, but by educators, community leaders, parents, and students themselves.

It demands a national conversation about what it means to be Kenyan—and whether that meaning can be taught, measured, and lived.

Nationhood Science represents more than an educational reform. It’s a calculated intervention aimed at rescuing a republic from its own cynicism. At its core is a belief that patriotism isn’t inherited—it’s learned. And if learned well, it could lay the foundation for a more united, informed, and accountable Kenya.

In classrooms across the country, a quiet revolution could begin. One where pencils and textbooks do more than prepare students for jobs—they prepare them for nationhood.

0 comments